Sustainability and climate impact are quite rightly becoming increasingly important factors for all businesses. The subject of setting carbon reduction strategies or carbon-neutral targets is no doubt consuming many leaders across all businesses.

Climate change is undoubtedly happening, and at an increasingly rapid rate. The Sixth Assessment report published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recognises the interdependence of climate, ecosystems, biodiversity and human societies. It emphasises the immediate need for a ‘now or never’ dash towards low-carbon economies and societies to limit global warming to 1.5ºC.

Recognising the need for change

This dash to low-carbon strategies presents real challenges for certain sectors of the economy. The issue of energy generation is an obvious one, but for the scientific sector, and more specifically, aseptic and sterile manufacturing, the additional challenges are immense.

In pharmaceutical manufacturing, there is a heavy reliance on many practices and products that are considered potentially not environmentally sustainable, but are essential to maintain the highly regulated, clean work environments needed to ensure final product safety. These include use of: single-use sterile disposable items; multilayer packaging; disinfectants; and cleanroom operations that have to run 24/7.

A switch from single-use sterile disposables presents many difficulties, as a crucial element here is sterility and the requirement to be 100% free of any contaminant

That said, the pharmaceutical industry recognises the importance of change, as highlighted in a poll in 2021, where 52% of respondents considered climate change as being the most pressing environmental issue. Furthermore, the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries & Associations refers to Environment, Health, Safety & Sustainability (EHS&S) practices and the commitments of the industry that are required to make real change. Consequently, the industry is reviewing and adopting a number of approaches to reduce environmental impact.

Sustainable options in single-use

A switch from single-use sterile disposables presents many difficulties, as a crucial element here is sterility and the requirement to be 100% free of any contaminant. Therefore, the most likely route to better practices must focus on the materials used and how these can be more sustainable, rather than eliminating use of single-use.

For example, it is possible to use recycled plastics to create the various parts of the single-use items themselves, together with more environmentally friendly materials within their packaging which can then be recycled.

Pack size considerations

The mantra of Reduce, Reuse, Recycle challenges us to minimise the use of single-use disposables. However, careful planning and avoiding waste can also have a positive impact where it is simply not possible to eliminate use of sterile disposables due the risk of contamination.

This is where suppliers need to prove their agility and flexibility by offering varying pack sizes to more closely match customer needs. For example, depending on requirements, a traditional pack of 10 poured media plates might always result in five being wasted. Whilst a switch to a pack of five will marginally increase the amount of packaging material consumed, it would avoid the environmental costs associated with the initial manufacture, transport and subsequent disposal of unused products as waste (Figure 2 on p20).

Glass vs plastic

Within the diverse range of consumables, one interesting and much debated area is the use of glass. In virtually all laboratories around the world there will be reagents, compounds and media stored in glass bottles. These are almost always single-use and then disposed of via recycling schemes. However, glass itself is an environmentally heavy product as it requires high amounts of energy to manufacture, transport and recycle.

Thought provokingly, the use of plastic instead of glass could be one possible solution to becoming more sustainable. Several reports and studies have sought to qualify the impact of glass versus plastic, with a view that single-use glass has a greater environmental impact than single-use plastic.

All parts of the supply chain must contribute in developing or sourcing alternatives

Ecochain, a solutions provider helping companies assess the environmental impact of their products, carried out some work for a client comparing the impact of a glass jar versus a PET (polyethylene terephthalate) equivalent. They concluded that whilst plastic has a poor image, the PET jar manufactured from recycled material had a significantly lower environmental impact than glass.

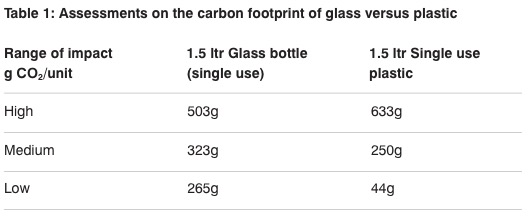

Furthermore, TappWater, an international business providing tap water filter solutions, also undertook some assessments on the carbon footprint of glass versus plastic, their estimates (high, medium and low) of the carbon footprint of each material are detailed in the table below.

Whilst this data suggests glass and plastic material have a similar carbon footprint, it doesn’t include the onward benefits of recycling. For glass this can be significant, with the potential of 26-40% reduction in carbon footprint, whereas for plastic a 30% reduction is suggested. This is because a challenge with plastics is the use of complex multi-layer materials which are difficult to recycle. However, the data also doesn’t include the impact of transportation, where glass can be up to x40 heavier than its plastic equivalent. This will undoubtedly lead to higher carbon emissions during transportation, when empty and when filled, creating a higher carbon footprint.

The evident ‘carbon expense’ of glass is a prime reason for adopting the use of plastic, and in some regions, such as Scandinavian countries, this is seen as a key factor to support the drive towards the United Nations 17 Sustainability Development Goals.

Here again manufacturers and suppliers must consider alternative solutions, for example the increasing use of recycled materials in the manufacture of plastic and the recyclability of that plastic, which of course can be reliant on the availability of local providers.

The ability and willingness of suppliers to develop new products to meet these needs is also a factor, as frequently new processes need developing to make a plastic bottled product. The research and development required can be surprisingly time intensive for what might seem a simple item.

An example being the supply of prepared media in bottles. A glass bottle is quite easy to autoclave, and has been the industry standard for decades, whereas its plastic equivalent requires subtle variations in process to produce a consistent high-quality product. Plastic bottles for autoclaving are now widely available (Figure 1 on p18).

Reducing energy consumption

As previously mentioned, another significant area of concern is energy consumption, particularly when running pharmaceutical clean rooms 24 hours a day, 7 days per week. These facilities are the bedrock of aseptic and sterile manufacturing which in turn ensures final product safety, and therefore any downgrade in their use must be very carefully considered.

One option where a cleanroom is not actually used 24/7 is to consider slowing the air handling systems. If the cleanrooms are unoccupied by personnel for large periods of time, for example overnight, reducing the airflow from the air handling units (AHU) can be a viable option.

For example, Janssen Vaccines in the Netherlands has implemented a schedule of reduced air flow when rooms are unoccupied and achieved up to 20% reduction in energy consumption. Whilst a significant amount of work and validation was required to confirm pressure recovery, as well as impact on temperature stability and of course impact on cleanliness levels, it has resulted in notable energy savings.

Conclusion

The challenges presented by over consumption and its impact on climate change are significant and our success in meeting these challenges will certainly define the 21st century.

All parts of the supply chain must contribute in developing or sourcing alternative low impact materials and practices, including increasing amounts of recycled material into finished products, minimising transportation ‘costs’ and reducing energy consumption. The pharmaceutical sector faces big challenges in meeting these needs whilst continuing to assure patient safety, but there are certainly options available and a strong desire to become more sustainable.