For years, there were warnings that a global pandemic was coming. Yet, when it struck the US healthcare system, the nation was woefully unprepared. With more than 880,000+ sick (at the time of press) and counting, hospitals are finding themselves at the breaking point. Horrific scenes are emerging of packed emergency rooms with not enough respirators, not enough workers, not enough ... anything ... to properly fight this disease.

State and local leaders, as well as health care workers themselves, have been repeatedly sounding the alarm over the dangerously low levels of personal protective equipment (PPE), one of the first lines of defence for the heroes caring for these vulnerable patients. Cities have ensued a worldwide search for masks, gowns and face shields, often competing against each other and driving up the cost of these vital supplies.

Coronavirus can survive for two to three days on plastic and stainless steel surfaces

All of this has unfolded against the larger backdrop of an explosion of coronavirus cases among healthcare workers. In the first week of April, Newsweek reported that over 100 nurses and doctors had died combating the coronavirus across the world. The article goes on to state that the infection rates among healthcare workers in Italy and Spain were reported to be 9% and 14%, respectively. And while it is still too early in the US to estimate the infection rate among health care workers, any increase in sick doctors and nurses threaten the response itself. Who will take care of us if health care workers cannot stay healthy?

But for all the focus on PPE, it isn't the only reason that hospital workers are getting sick. COVID-19 is a virulent virus that can remain stable for several hours to days in aerosols and on surfaces. According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the coronavirus can survive for two to three days on plastic and stainless steel surfaces like doorknobs and bedframes or food trays and light switches. The virus can also last for up to 24 hours on cardboard surfaces like tissue boxes. More concerning is that the coronavirus can also linger for hours in the air.

In 49 operating rooms more than half of objects were overlooked

To fully protect workers, hospitals and healthcare settings need to employ real-time environmental screenings that will detect COVID-19 in both the air and on surfaces. If detected, rapid remediation technologies need to be used to kill the virus. Screening is a powerful intervention strategy that can contribute to a reduction in transmission and infection - yet it is seldom performed. More disturbing, hospitals themselves aren't even cleaned regularly, and there's no oversight or standard for monitoring health care environments.

Germ coated

At one time hospitals did test surfaces, but in 1970, the CDC and the American Hospital Association advised against it. The agencies stated that it was unnecessary and not cost-effective. Since then, MRSA infections have increased 32-fold, and numerous studies have linked unclean hospital equipment and rooms to other infections. Boston University researchers who examined 49 operating rooms found that more than half of the objects that should have been disinfected were overlooked. A study of patient rooms in 20 hospitals in Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Washington, D.C., found that more than half the surfaces that should have been cleaned for new patients were left dirty.

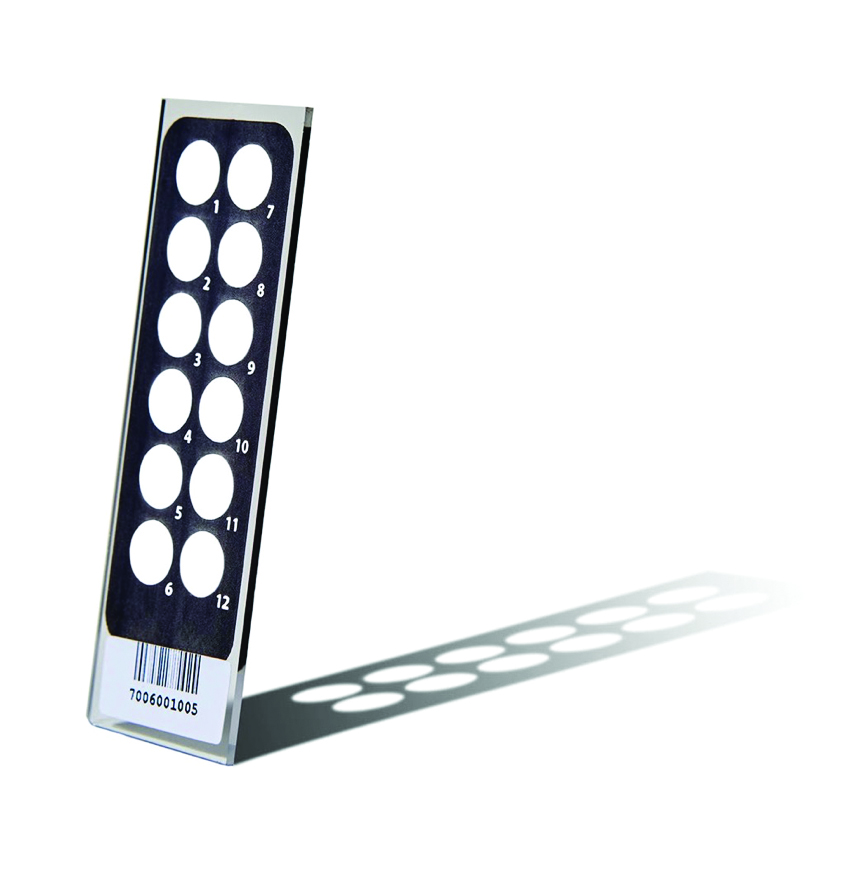

PathogenDx EnviroX-Rv kit

These findings were presented during a Congressional Hearing on Hospital Infection that led the CDC to defend itself by stating it relies on State legislation to enforce compliance with guidelines. New Jersey, Illinois and Pennsylvania have all legislated for screening separately, but there is no concerted -or mandatory- approach.

In 2005, health officials in Ireland and Scotland implemented a programme to rate hospitals in terms of cleanliness; red (the dirtiest), yellow or green. After releasing the first-year ratings, hospitals with low ratings were pressured into cleaning up their game - literally - and most did by the time the 2006 results were released.

Alive and airborne

Surfaces aren't the only thing to contend with when it comes to COVID-19. Because evidence shows the virus is aerosol, even the air in hospitals is suspect. Scientists previously thought that the viral droplets were dead, but new research shows that they are simply dormant and waiting for a new source of rehydration.

PathogenDx MicroArray

In fact, Stephanie Taylor, a Harvard Medical School lecturer, studied the effect of hospital environments on human health and found that when air is dry, "droplets and skin flakes carrying viruses and bacteria are launched into the air, travelling far and over long periods of time. The microbes that survive this launching tend to be the ones that cause healthcare-associated infections." It turns out that humans are an ideal source of hydration - made up of 60% water. Compounding exposure, dry air also interferes with our natural immune barriers, humid in nature, which makes us even more susceptible to infection.

While the NIH is still studying the issue, other studies seem to confirm her findings. A team at the Mayo Clinic humidified half of the classrooms in a preschool and left the other half alone over three months during the winter. Influenza-related absenteeism in the humidified classrooms was two-thirds lower than in the standard classrooms.

Further, many older hospitals, especially those found in urban areas, lack effective ventilation systems or negative-pressure patient rooms that can filter out airborne contaminants. Many built before the 1950s, these older hospitals have simply not made the type of upgrades to their systems over time that would mitigate the amount of contaminated air circulating on the inside of a hospital.

A better response

The solution to protecting health workers against COVID-19 requires a multi-faceted approach. In addition to the well-established need for PPE, we also need to ensure that hospitals have sterile environmental conditions.

Consumers have been asked to safeguard their personal spaces by washing their hands, wiping down groceries and standing at least six feet apart from others to avoid spreading infection and getting sick themselves. Now hospital administrators and state and local leaders must do their part, implementing a more careful and measured "search and destroy" policy for COVID-19 in the facilities housing our sickest and the people caring for them.

The solution to protecting health workers against COVID-19 requires a multi-faceted approach

The technology to implement this strategy exists today. Aerosol and surface swab samples can be processed in under six hours, testing not only for COVID-19, but also Influenza A & B, as well as MERS and Norovirus. These rapid tests are 12 times faster than older qPCR tests that often took two to three days to detect viruses and were more expensive, as well. Bioaerosol devices are able to take air samples that can also rapidly test for the presence of infectious microbes. This would provide an aggressive screening technique, allowing hospitals and healthcare settings to isolate and decontaminate positive areas.

Without guidance from the CDC, health care leaders and advocates must ensure hospitals remain places where people get better - not facilities that risk further threaten public safety. Advanced surface and environmental testing technology used in tandem with PPE can help hospital staff stay safe - for their sake and ours.

N.B. This article is featured in the XYZ 2020 issue of Cleanroom Technology. The latest digital edition is available online.