Cleaning and disinfecting in the food industry is a crucial part of the production cycle; these activities can have devastating consequences if not done properly. Both form the basis of being able to deliver and guarantee a safe end product. However, it is not an easy task.

To do an effective and thorough clean, the first step is to understand the various soiling or residue challenges that need to be addressed. These could be organic or inorganic in nature.

Christeyns Food Hygiene believes this is very much a case of tailoring cleaning solutions to meet each individual customer; one size does not fit all.

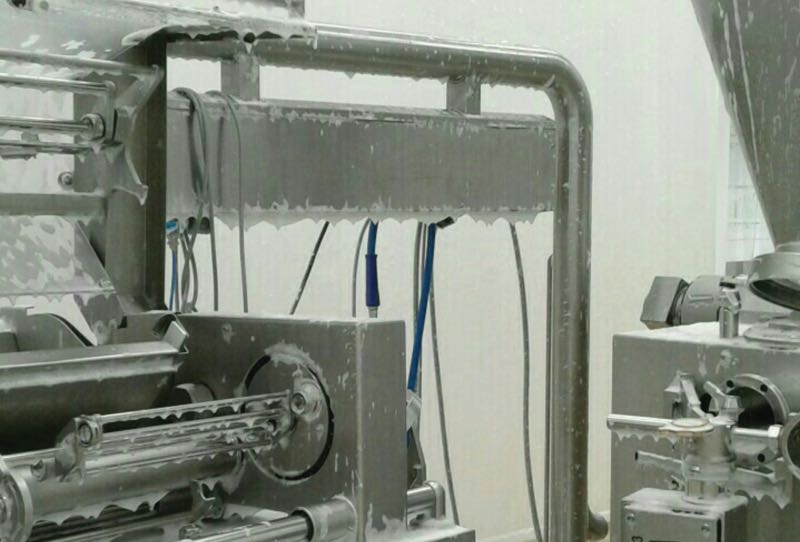

Good customer research is essential and involves lots of questions regarding the business and routines already in place. A visit to the site is always the best option to collect information on how the equipment is cleaned (automatically or by hand), what facilities are available, and whether the staff performing the task is well trained or an external professional team carries out the clean.

The modern cleaning regime is: rinse away debris, clean using detergents, rinse again and then disinfect the ‘clean’ surface using a specialised, approved disinfectant

Other things to note are the type of materials present: all stainless/plastic or are there soft metals present, which need to be protected? What is the hardness of the water used to clean? This can range from very hard to very soft but it makes a difference to the choice of a suitable alkaline detergent. Also important is the process for the spent detergent and soiling during the cleaning process.

It is worth noting that cleaning and disinfecting are two separate things. Effective cleaning is the complete removal of soils and residues from surfaces, leaving them visually clean so that the second stage, disinfection, can be effective. Surfaces will be free from soil, but microorganisms remain. Using validated disinfectants on surfaces, following the instructions and contact times, reduces microorganisms to acceptable levels for food production, so they do not pose a threat to health.

The modern cleaning regime is: rinse away debris, clean using detergents, rinse again and then disinfect the ‘clean’ surface using a specialised, approved disinfectant. Detergents are used to remove soil (a mixture of food waste and bacteria) from the surface of processing equipment, floors or walls.

Tackling soils and residue

The action of the detergent solution is to suspend the food waste and bacteria mixture away from the surface and allow it to be rinsed off into the drain. As there are many types of soil, the cleaning procedure and detergent is different for each one.

The most common soils (carbohydrates like sugar, starch and cellulose) are the easiest to remove, but proteins like meat, milk and eggs, are probably the most difficult because changes in heat and pH alter the structure of the protein and bind it to other molecules, increasing their tenacity and often leaving them insoluble.

Fatty soils are not water-soluble and pose a greater challenge than carbohydrates. It is necessary to use alkaline cleaners in this instance with high temperatures that are above melting point.

Mineral salts, the inorganic food soil, lead to scale formation on equipment so acidic cleaners are required to remove these efficiently.

When selecting a disinfectant, it is important to also look at its toxicity, leftover residues and the impact of water hardness

Four variables within the cleaning process can impact soil removal: detergent/concentration; time; temperature; and physical action. When selecting a disinfectant, it is important to also look at its toxicity, leftover residues and the impact of water hardness. Again, temperature is important because some disinfectants may not be as effective in cold environments. The chemicals used to clean and disinfect depends very much on the type of product being produced, for example dairy, meat or brewing, and the production environment.

There are a few golden rules to follow. Brewers dislike quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) because these disinfectants stick to certain surfaces, especially glass, and can adversely affect beer head retention. There are also potential issues if cleaning a fermenting vessel using caustic soda due to the residual presence of CO2 gas.

However, highly caustic detergents, based on sodium or potassium hydroxide, are common in a dairy as they saponify, or breakdown, insoluble milk fats. In the food industry, soiling can be very high in grease and fats, and these respond well to the use of surfactants; the traditional washing-up liquid. Where proteins may be present, chlorinated detergents have distinct advantages.

It is important to know your customer and know their business, to get the chemical mix right. If the chemical balance is not correct, the outcome could be a poor clean with a risk of cross-contamination. Time, money and natural resources are easily wasted in these circumstances.

There is also the risk of allergens being left behind; other residues could also affect the next product through the plant altering the colour, causing taste carry over, introducing seeds or foreign bodies. Any residues after a clean also contribute to a poor disinfection stage, leading to further issues such as a reduced shelf life for the next product being processed through the plant.

Detergents: Get it right

Too much detergent, however, means higher production costs and possible effluent issues as cleaning chemicals have to be neutralised to meet an existing trade effluent consent, agreed with the local wastewater authority. The cleaning equipment itself also needs to be considered. If a foam detergent is to be used, is the equipment good enough? Cheap equipment can produce a disappointing wet foam, which does not give the required contact time. It is important to balance the size of the foam unit against the size of the cleaning task.

Some detergents can be automatically dosed and their strength controlled using conductivity and engineering equipment. Otherwise, manual checks are important to verify that detergents are being used at their recommended concentrations: lab methods, quick field dropper test kits, and even expensive test strips are available to help do this. Specialist kits are also available to check for individual residues, for example ATP, but it is important to understand exactly what these kits are measuring and what the results mean.

A surface is chemically clean if there are no microscopic residues of soil remaining and no residual detergents or disinfectant chemicals to contaminate the food product.

Determination of chemical cleanliness requires tools and not just the human eye. This monitoring is crucial for optimum outcomes and to tweak the chemical mix when necessary. Getting the chemical mix right means using less water and power in the process. Water is an increasingly costly item; it has to be paid for, heated, cooled, treated and then paid for again in disposal. It makes environmental and economic sense to monitor its use from start to finish.

Food processing company Finnebrogue has developed its hygiene standards working with Christeyns to meet the exacting requirements of the retail customers. Declan Ferguson, technical director, comments: “We have addressed and exceeded challenges relating to the cleaning and disinfection of our plant equipment from managing allergens and species cross-contact to the bespoke development of management strategies, so as to protect the integrity of our nitrite free range of Naked Bacon.”

This article appeared in the September issue of Cleanroom Technology.