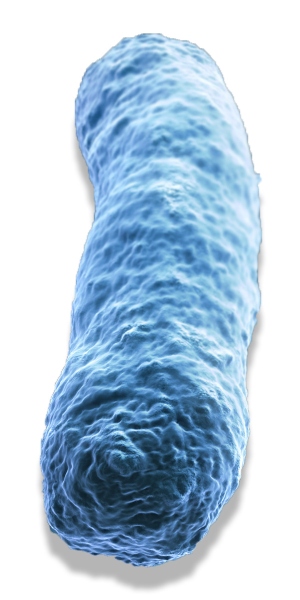

Legionella are aquatic bacteria that are common in natural water sources such as rivers, lakes and reservoirs, but usually in low numbers. They may also be found in purpose-built water systems, and it is here that they pose the most risk to human health. With their concentrated populations of high-risk individuals, hospitals and healthcare facilities are the greatest concern for public health. The risk is particularly severe for immuno-compromised individuals, including intensive care patients and those suffering from diabetes.

Person-to-person spread has hardly ever been reported the threat comes from water systems, where bacteria including Legionella can build up in biofilms in plumbing “dead legs”, around outlets, and in other high-risk areas. As biofilm forms, microorganisms proliferate, and sections may break off as ‘planktonic’ waterborne components. These free-floating forms of Legionella have the potential to seed new biofilm colonies elsewhere in a water system, or to emerge in a potentially infectious aerosol.

Legionnaires’ disease is a rare pneumonia

Aerosols may be released indoors from flushed toilets, running taps and showers, or in the wider environment, from a cooling tower releasing contaminated aerosols. Depending on environmental conditions, Legionella in aerosols can survive for long periods, and have been estimated to travel up to three miles in contaminated water droplets released from cooling towers.

Legionnaires’ disease

First named in 1976 as the cause of an outbreak of severe pneumonia in a convention centre in the US, Legionnaires’ disease is caused by Legionella, and remains a significant notifiable health concern. Legionnaires’ disease is a rare pneumonia, diagnosed through laboratory investigations of sputum and urine. If administered in a timely way, patients can be treated successfully with antibiotics, however, approximately 1 in 10 cases are fatal and the disease often causes long-lasting symptoms for survivors.

The Legionella bacterium also causes Pontiac fever, which is a milder flu-like illness resembling the flu and often clears on its own without medication. The two illnesses are sometimes referred to as legionellosis.

There are approximately 60 species of Legionella, and of these, 20 species have been linked to one or more cases of human disease worldwide, but the strain Legionella pneumophila is by far the most common human pathogen and is the main cause of Legionnaires’ disease. Official statistics from Public Health England published December 2017 note that in 2016, there were 355 recorded confirmed cases of Legionnaires’ disease in England and Wales, of which 99.7% were caused by Legionella pneumophila.

The need for testing for Legionella

Eradicating Legionella contamination from any building is very difficult, but there are measures, such as careful choice of materials in piping, that can help to minimise the build-up of biofilm. An important control is to keep stored hot water temperatures high, at least to 60°C, distributing it at 50°C and, in hospitals, at 55°C, and to ensure that cold water stays cold, ideally below 20°C. Keeping water moving in the system is also important as it reduces stagnation. If outlets are not used regularly, proactive flushing regimes need to be implemented and the application of suitable biocides might also be necessary.

To ensure these measures are effective, facilities managers need to monitor water regularly.

‘The Lancet’ outlines why Legionnaires’ disease is one of the issues of which facilities managers need to be constantly aware, stating: “Legionnaires’ disease is an important cause of community-acquired and hospital-acquired pneumonia. Although uncommon, Legionnaires’ disease continues to cause disease outbreaks of public health significance.”

Testing methods

The traditional ‘gold standard’ method for measuring the presence of Legionella in water samples is a complex plate culture test involving numerous steps that can take up to 14 days to provide confirmed results. The test has been in use for over 30 years and, despite improvements, has limitations, including a lack of sensitivity and reproducibility.

The plate culture testing protocol requires large sample volumes of up to a litre. Bacteria are concentrated using centrifugation or membrane filtration, processes that may damage, or even destroy, the bacteria, making results unlikely to represent the true levels of contamination. The organisms are then re-suspended and culture plates are inoculated, then incubated for 10 days.

Multiple plates are incubated, with the result taken from the ‘best’ plate, chosen by the technician, a decision that is highly subjective as it depends on the experience and expertise of the analyst. A secondary confirmation test is needed before final results can be reported, lengthening the overall testing time.

Non-target bacteria in the sample may overwhelm slower growing Legionella and plates that are overgrown may be characterised as “presence of background flora” and discarded without establishing whether Legionella pneumophila was present in the sample, potentially wasting valuable time and resources.

It is unclear whether or not even modern PCR methodologies can effectively distinguish between dead and live

To counteract the problem of plates becoming overwhelmed, the media usually contain antibiotics to improve selectivity over non-Legionella species. However, different laboratories use different media, agar and filters, introducing significant variability. Variability has even been demonstrated between different batches of media from the same manufacturer. In addition, protocol implementation is very technician-dependent; as is the decision of which incubated plates to enumerate. As such, results can even vary between the same technician on different runs. With so many sources of variability, it is difficult to generate sufficiently reproducible results over time to make informed water management decisions.

Each of the aforementioned preparation steps represents opportunities for loss of bacteria in the sample, and when combined with the variability of methodologies, the inconsistency of competing bacteria, and the subjective nature of decision making and plate reading, the cumulative measurement uncertainty is significant. With the plate method, it is inherently difficult to achieve the reproducible and consistent results needed for trending over time and making informed water management decisions.

The UK Health and Safety Executive (UK HSE) offers guidance on testing for Legionella and monitoring water quality, however it does concede that, “Legionella culture methods do have certain acknowledged disadvantages including [a] long incubation period; poor reproducibility; poor sensitivity; inability to detect viable but non-culturable cells; and inhibition due to competing microbial flora.” Bio Med Central Microbiology concludes that the “drawbacks of culture-based methodology used for Legionella enumeration can have great impact on the results and interpretation which together can lead to underestimation of the actual risk.”

New tests to prevent disease

The book, ‘Detection of Pathogens in Water using Micro and Nano-Technology, by Giampaolo Zuccheri and Nikolaos Asproulis, has a section on ‘Immunodetection and Legionella fast detection’ which lists a number of alternative testing solutions.

The plate culture testing protocol requires large sample volumes of up to a litre

More recently, the development of significantly faster, more sensitive testing protocols provide more options for detection, but these also have their downsides. For example, a technique such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing can detect and quantify bacterial DNA with great sensitivity. However, the signals it provides (genomic units/l) cannot be interpreted readily against recognised action levels that reflect traditional plate culture and are expressed as colony forming units (CFU)/l. Additionally, it is unclear whether or not even modern PCR methodologies can effectively distinguish between dead and live, potentially dangerous Legionella.

There are also liquid culture alternatives that remove many of the subjective and variables of traditional spread plate testing – as well as giving faster results. One such method is the IDEXX Legiolert (registered trademark) test that is based on a bacterial enzyme detection technology that specifically signals the presence of Legionella pneumophila, and delivers confirmed results in 7 days without additional steps. The method can also be used to quantify contamination using a most probable number (MPN) table, which is a statistical expression of the most likely concentration in the original sample. MPN values are equivalent to the CFU values derived from traditional testing and are analogous to the action limits advocated in UK, European and U.S. guidelines.

Although the UK guidelines HSG274 Parts 1, 2 and 3, “Legionnaires’ disease: Technical guidance”, published by the HSE do not specify individual species of Legionella, in practice, Legionella pneumophila should be considered the main concern, because this is the primary causative agent of Legionnaires’ disease.

Prevention is key

Legionnaires’ disease poses a great threat to public health, and in hospitals especially, can have devastating effects. Preventing Legionella contamination is the best policy to reduce the risks, but any steps taken must be validated by a testing regime that is fast and reliable. It is evident that there are many drawbacks to the current ‘gold standard’, many of which can be overcome with new liquid culture methods offering solutions, which offer rapid and consistent results in an economical manner.